Have you ever considered the delicate balance between your nightcap and your night’s sleep or your afternoon cup of coffee and catching Z’s? Sleep is a fundamental pillar when it comes to supporting our health, longevity, and overall well-being. However, our cherished beverages—alcohol and caffeine—harbor both subtle and not-so-subtle effects on our sleep patterns. Let’s pore over the science to understand better how the contents of your cup can influence your sleep.

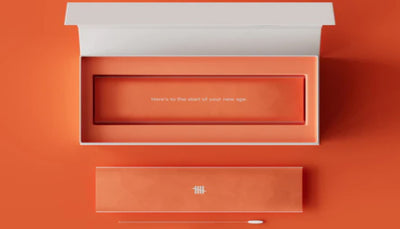

Your best night’s sleep starts now. Tally’s sleep supplement, Restore, is a specially formulated blend of L-theanine, magnesium bisglycinate chelate complex, and apigenin that is designed to help you fall asleep faster, stay asleep longer, and wake up feeling refreshed and energized (with the bonus of providing pro-longevity benefits).

Caffeine and sleep

The perks and pitfalls of caffeine on sleep

Americans now favor coffee over any other drink, even water, and it’s not just about the taste [1]. Studies suggest that coffee offers vast health benefits, ranging from reduced risks of cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases to lower all-cause mortality rates [2]. Interestingly, in regular coffee drinkers, caffeine from coffee activates areas of the brain involved in short-term memory, attention, and focus, whereas caffeine on its own does not [3], which means that there are more perks to your morning coffee ritual beyond merely getting life-giving caffeine into your body (indeed, coffee contains more than 1,000 different molecules!).

However, while your morning coffee might kickstart your day by blocking sleep-promoting adenosine, indulging too late can disrupt your body’s natural circadian rhythms [4]. Caffeine acts as an adenosine receptor antagonist, blocking sleep-promoting signals in the brain; this is how caffeine works to increase alertness and promote wakefulness. One study found that drinking the equivalent of a double espresso (400mg of caffeine) up to six hours before bed shifted participants’ internal clock back by around 40 minutes [4].

This circadian rhythm shift poses challenges for maintaining healthy sleep patterns but suggests coffee’s potential for managing circadian rhythm problems such as jet lag. Furthermore, caffeine consumption has been reported to reduce total sleep time by 45 minutes and sleep efficiency by 7%, with an increase in sleep onset latency of 9 minutes and a decrease in deep sleep, a sleep stage that’s important for repairing and building new bones, muscles, and tissues, regulating glucose metabolism, and supporting immune system function [5]. Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors, which can lead to trouble falling asleep, difficulty falling asleep, and problems staying asleep, especially in caffeine consumers or those with high daily caffeine intake. High doses of caffeine, such as those found in some energy drinks, can have a negative effect on sleep quality and may contribute to chronic insomnia, disruptions in the sleep wake cycle, or other sleep disorders or problems.

Of course, 400mg of caffeine consumption is a fairly high dose—the average cup of coffee contains around 80-100mg—so caffeine’s timing, dose, and impact on sleep require further study. Caffeine content varies widely between products due to many factors such as the type of coffee beans, tea leaves, preparation method, and serving size. Coffee beans and tea leaves are primary natural sources of caffeine, and how much caffeine is present depends on caffeine levels in the specific product. Monitoring daily caffeine intake is important for minimizing sleep disruption, as excessive intake can lead to sleep problems.

Both the timing and amount (caffeine dose) of caffeine administration can significantly affect sleep architecture and perception. Energy drinks often contain high doses of caffeine and other stimulants, which can further disrupt sleep. Caffeine tolerance can develop in regular caffeine consumers, reducing its effectiveness in increasing alertness and potentially leading to higher caffeine doses and greater risk of sleep problems. Older adults are more sensitive to caffeine's sleep-disrupting effects and may need to be especially cautious.

What is the optimal timing for caffeine consumption?

Caffeine peaks in the bloodstream within 30-60 minutes post-consumption and has an average half-life of around 5 hours, meaning caffeine can stay in the system for more than 10 hours. The body takes this amount of time to eliminate half of the caffeine consumed, which is why timing your intake is crucial. Factors such as genetics and medication affect caffeine’s metabolism [6]. For example, oral contraceptives slow down caffeine breakdown, prolonging its presence in the body [7]. Gene variations—specifically, the CYP1A2 and ADORA2A genes—also identify individuals as either fast or slow caffeine metabolizers, which can impact sensitivity to caffeine and sleep quality [8].

Research suggests that caffeine consumption should be stopped at least 8 hours before bedtime to minimize sleep disruption and improve one's ability to fall asleep, and caffeinated pre-workouts should be consumed at least 13.2 hours before bedtime [5]. Those sensitive to caffeine or experiencing sleep issues may want to avoid caffeine at least 10 hours before sleep. For most people, a helpful rule of thumb is to avoid caffeine after noon. Appropriate consumption timing is key to minimizing sleep disruption and maintaining a healthy and consistent sleep schedule. Failing to follow appropriate consumption guidelines can increase the risk of adverse events related to sleep and overall health.

Interestingly, despite coffee’s wakefulness-promoting properties, its efficacy diminishes with consecutive nights of insufficient sleep (5 hours or less), underscoring the importance of quality sleep over caffeine reliance for optimal next-day functioning [9].

Alcohol and sleep

Sleep under the influence: How alcohol affects sleep

After a long day, you may reach for a glass of wine or a nightcap to help you unwind before bed; however, more and more research is highlighting the adverse effects that alcohol can have on sleep. While it’s true that drinking alcohol may help you fall asleep faster, which is certainly part of its appeal, it also disrupts your normal sleep cycle by suppressing REM sleep during the first half of the sleep cycle, which is essential for learning, memory, emotional processing, and waking up feeling refreshed [10, 11]. Alcohol also leads to more sleep disruptions throughout the night and can decrease melatonin production [11, 12, 13]. Even in individuals who felt rested, alcohol still reduced next-day performance and alertness [14].

One study found that alcohol intake was associated with increased sympathetic regulation (our body’s “flight or fight” response) and impacted cardiovascular relaxation during sleep, regardless of gender. These results were observed even in low alcohol intake (less than two drinks per day for men and less than one drink per day for women) [16]. Even men who had fewer than two servings of alcohol per day and women who had fewer than one serving of alcohol per day still experienced a 9.3% decrease in sleep quality. Higher amounts of alcohol consumption were associated with a 24-39.2% decrease in sleep quality.

Is there a right hour for happy hour?

The ideal approach is to minimize or avoid alcohol consumption to safeguard your sleep. However, if you do decide to indulge, it's crucial to understand the time your body requires to metabolize alcohol. Alcohol reaches its peak levels in the bloodstream approximately 60-90 minutes after consumption. Its half-life extends to about 4-5 hours, but for the body to fully metabolize alcohol, it necessitates roughly five half-lives, equating to about 25 hours [ 16]. Thus, despite recommendations to refrain from alcohol consumption 3-4 hours before sleep, this duration still falls short of fully clearing alcohol from your system before bedtime.

Research indicates that even consuming a moderate amount of alcohol six hours before sleep can diminish total sleep time, delay sleep onset, and reduce REM sleep while significantly increasing wakefulness in the latter part of the night [ 17]. While further research is necessary to ascertain if consuming alcohol more than six hours before bedtime exerts similar detrimental impacts on sleep quality, it's evident that alcohol, particularly when consumed in the evening, adversely affects sleep.

Eye-opening findings: The latest on alcohol and caffeine’s negative effects on sleep

The present study examined the combined effects of caffeine and alcohol on sleep quality. Participants were instructed to keep a sleep diary, recording their sleep patterns, quality, and any obstacles over a six-week period. They also reported whether they had consumed caffeine during the study period, as well as their alcohol intake.

The study found that caffeine and alcohol, when consumed separately, detrimentally affected sleep. Specifically, caffeine shortened sleep duration by 10 minutes for each cup consumed, while alcohol reduced perceived sleep quality by 4% per drink. However, those who reported consuming both caffeine during the day and alcohol at night found that the psychoactive properties of caffeine and the sedative properties of alcohol canceled each other out and, thus, did not impact sleep quality or quantity [18].

Although these findings from the present study are fascinating and merit further investigation, they should not be interpreted as an endorsement for using alcohol in the evening to counteract the stimulating effects of daytime caffeine consumption. Instead, these results highlight the complex cycle of self-medication, especially among individuals experiencing high levels of stress in their personal or professional lives.

It’s also crucial to note that this study relied on self-reported sleep diaries, which may not accurately reflect sleep quality. Comprehensive sleep studies are necessary to fully comprehend the combined impact of caffeine and alcohol on sleep.

Science-backed tips to enhance sleep quality

While the amount of sleep we get is crucial for mental health, the quality of that sleep is perhaps even more vital in alleviating stress, anxiety, and depression. Practicing good sleep hygiene, such as maintaining a consistent bedtime routine, is essential for improving sleep and achieving a good night's rest. Sleeping in a cool, dark, and quiet environment can also have a strong impact on overall sleep quality. These strategies can also help address common sleep problems that may interfere with restorative sleep. It’s widely recognized that minimizing exposure to blue light and ensuring our sleeping environments are quiet, dark, and cool can enhance sleep quality. However, what additional steps can we take during the day to ensure a restful night’s sleep and consequently, a happier and more stable mood? Here’s some science-backed support to enhance the quality of deep and REM sleep:

Get outside in the sun:

The importance of daily sun exposure cannot be overstated, as research indicates it significantly enhances sleep quality and patterns [20]. This is especially true for the elderly, who typically produce less melatonin, yet reported that daily sun exposure improved their sleep [21]. Additionally, older adults are more sensitive to caffeine's sleep-disrupting effects and should be cautious with caffeine intake. Moreover, spending just 20-30 minutes in nature can markedly decrease stress and anxiety, while also alleviating symptoms of depression [22, 23].

Support a healthy gut microbiome:

One study found that certain gut bacteria—Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes—were associated with better sleep efficiency, while other bacteria—Lachnospiraceae, Corynebacterium, and Blautia—negatively impact sleep efficiency. These findings suggest that our gut could impact our sleep, which isn’t too surprising, given that more than 90% of serotonin in our bodies is synthesized in our guts [24]. Support your gut by avoiding alcohol, sugar, and ultra-processed foods and eating a balanced, diverse whole-food diet that is rich in prebiotics and probiotics. Fermented foods such as yogurt, sauerkraut, natto, and kimchi can also help improve microbiome diversity [25].

Prioritize daily exercise:

Whether you love lifting weights, hiking, or going for a bike ride, engaging in regular physical activity (exercise) increases your sleep need, which also improves sleep quality. Research even shows that regular exercise can help people with insomnia experience better sleep [26]. People who engaged in at least 30 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise saw a difference in their sleep that night, which means you don’t have to exercise for weeks or even months to start reaping the sleep benefits.

Boost your fiber intake:

While we should be getting anywhere from 25 to 30 grams of fiber a day, most Americans are only getting around 15 grams [27]. Prioritizing and tracking daily fiber intake may actually help you get better sleep. Research shows that increased fiber intake was associated with greater deep sleep [28]. Conversely, diets low in fiber and high in sugar and saturated fat were associated with lighter, less restorative sleep [29].

Consume a plant-rich diet:

Studies have shown that plant-rich diets may have an indirect effect on sleep quality by improving depression [30]. A recent study also found that while overall protein intake did not have an impact on sleep, plant protein may improve sleep quality, while certain types of animal protein may disrupt sleep [31]. This may be because red meat is high in saturated fat, which may result in less restorative sleep, or because animal protein takes longer to digest. Therefore, it may be a good idea to incorporate high-quality plant protein at dinnertime to see if it improves your sleep.

Be strategic about naps:

While a quick 20 to 30-minute nap can improve cognition, productivity, and mood [32, 33, 24], if you find yourself needing to take naps regularly, this could be a sign that you’re not getting enough sleep at night and may need a more consistent sleep schedule. Furthermore, studies have shown a positive correlation between daytime napping and depression in adults ages 45-65 [35]. If you do plan to take a nap, make sure that you’re not sleeping longer than 30 minutes and that your nap is at least 4-6 hours before bedtime. Sleep experts say that the ideal nap time is between 1pm to 3pm [36].

Promote better sleep with Restore

Looking to boost sleep quality and quantity? Restore sleep supplement by Tally Health supports healthy aging and is designed to help you fall asleep faster, sleep more deeply, and wake up feeling rejuvenated.

How does caffeine interrupt sleep?

Caffeine blocks adenosine, a chemical that makes you feel sleepy, and can delay the timing of your internal clock, making it harder to fall asleep.

When should I stop drinking coffee for a good night’s sleep?

Experts recommend stopping caffeine at least 8 hours before bedtime to avoid disrupting your sleep.

Does caffeine affect everyone’s sleep the same way?

No, sensitivity to caffeine varies by individual, depending on factors like genetics, age, and overall caffeine tolerance.

Recommended Supplements

Citations

[1] French, R. (2022, June 2). Coffee consumption hits record high in US. Food & Beverage Insider. https://www.foodbeverageinsider.com/beverage-development/coffee-consumption-hits-record-high-in-us

[2] Harvard School of Public Health. (2020). Coffee. The Nutrition Source. Retrieved from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/food-features/coffee/

[3] Magalhães, R., Esteves, M., Vieira, R., Castanho, T. C., Amorim, L., Sousa, M., Coelho, A., Moreira, P. S., Cunha, R. A., & Sousa, N. (2023). Coffee consumption decreases the connectivity of the posterior Default Mode Network (DMN) at rest. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 17, 1176382. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2023.1176382

[4] Burke, T. M., Markwald, R. R., McHill, A. W., Chinoy, E. D., Snider, J. A., Bessman, S. C., & Jung, C. M. (2015). Effects of caffeine on the human circadian clock in vivo and in vitro. Science Translational Medicine. https://doi.org/aac5125

[5] Gardiner C, Weakley J, Burke LM, Roach GD, Sargent C, Maniar N, Townshend A, Halson SL. The effect of caffeine on subsequent sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2023 Jun;69:101764. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101764. Epub 2023 Feb 6. PMID: 36870101.

[6] Cappelletti, S., Daria, P., Sani, G., & Aromatario, M. (2015). Caffeine: Cognitive and Physical Performance Enhancer or Psychoactive Drug? Current Neuropharmacology, 13(1), 71-88. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X13666141210215655

[7] Ribeiro-Alves, M. A., Trugo, L. C., & Donangelo, C. M. (2003). Use of Oral Contraceptives Blunts the Calciuric Effect of Caffeine in Young Adult Women. The Journal of Nutrition, 133(2), 393-398. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/133.2.393

[8] Kapellou A, King A, Graham CAM, Pilic L, Mavrommatis Y. Genetics of caffeine and brain-related outcomes - a systematic review of observational studies and randomized trials. Nutr Rev. 2023 Nov 10;81(12):1571-1598. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuad029. PMID: 37029915.

[9] Doty TJ, So CJ, Bergman EM, Trach SK, Ratcliffe RH, Yarnell AM, Capaldi VF 2nd, Moon JE, Balkin TJ, Quartana PJ. Limited Efficacy of Caffeine and Recovery Costs During and Following 5 Days of Chronic Sleep Restriction. Sleep. 2017 Dec 1;40(12). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx171. PMID: 29029309.

[10] McCullar, K. S., Barker, D. H., McGeary, J. E., Saletin, J. M., Swift, R. M., & Carskadon, M. A. Altered sleep architecture following consecutive nights of presleep alcohol. Sleep. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsae003

[11] Park, Y., Oh, K., Lee, S., Kim, G., Lee, J., Lee, H., Lim, T., & Kim, Y. (2015). The Effects of Alcohol on Quality of Sleep. Korean Journal of Family Medicine, 36(6), 294-299. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.2015.36.6.294

[12] Colrain, I. M., Nicholas, C. L., & Baker, F. C. (2014). Alcohol and the Sleeping Brain. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 125, 415. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-62619-6.00024-0

[13] Rupp TL, Acebo C, Carskadon MA. Evening alcohol suppresses salivary melatonin in young adults. Chronobiol Int. 2007;24(3):463-70. doi: 10.1080/07420520701420675. PMID: 17612945.

[14] Stein, M. D., & Friedmann, P. D. (2005). Disturbed Sleep and Its Relationship to Alcohol Use. Substance Abuse : Official Publication of the Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse, 26(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1300/j465v26n01_01

[15] Pietilä J, Helander E, Korhonen I, Myllymäki T, Kujala UM, Lindholm H. Acute Effect of Alcohol Intake on Cardiovascular Autonomic Regulation During the First Hours of Sleep in a Large Real-World Sample of Finnish Employees: Observational Study. JMIR Ment Health. 2018 Mar 16;5(1):e23. doi: 10.2196/mental.9519. PMID: 29549064; PMCID: PMC5878366.

[16] Cleveland Clinic. (2021). How Long Does Alcohol Stay in Your System? Retrieved from https://health.clevelandclinic.org/how-long-does-alcohol-stay-in-your-system/

[17] Landolt HP, Roth C, Dijk DJ, Borbély AA. Late-afternoon ethanol intake affects nocturnal sleep and the sleep EEG in middle-aged men. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996 Dec;16(6):428-36. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199612000-00004. PMID: 8959467.

[18] Song, F., & Walker, M. P. (2023). Sleep, alcohol, and caffeine in financial traders. PLOS ONE, 18(11), e0291675. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291675

[20] Lee, H., Kim, S., & Kim, D. (2014). Effects of exercise with or without light exposure on sleep quality and hormone reponses. Journal of Exercise Nutrition & Biochemistry, 18(3), 293-299. https://doi.org/10.5717/jenb.2014.18.3.293

[21] Mishima, K., Okawa, M., Shimizu, T., & Hishikawa, Y. (2001). Diminished melatonin secretion in the elderly caused by insufficient environmental illumination. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 86(1), 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.86.1.7097

[22] Harvard Health Publishing. (2019). A 20-minute nature break relieves stress. Harvard Health. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/a-20-minute-nature-break-relieves-stress

[23] Shanahan, D. F., Bush, R., Gaston, K. J., Lin, B. B., Dean, J., Barber, E., & Fuller, R. A. (2016). Health Benefits from Nature Experiences Depend on Dose. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28551

[24] Barandouzi, Z. A., Lee, J., Chen, J., Henderson, W. A., Starkweather, A. R., & Cong, X. S. (2022). Associations of neurotransmitters and the gut microbiome with emotional distress in mixed type of irritable bowel syndrome. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05756-0

[25] Weaver, J. (2021, July). Fermented-food diet increases microbiome diversity, decreases inflammatory proteins, study finds. Stanford Medicine News Center. Retrieved from https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2021/07/fermented-food-diet-increases-microbiome-diversity-lowers-inflammation

[26] Gamaldo, C. (n.d.). Exercising for better sleep. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/exercising-for-better-sleep

[27] McKeown, N. M., & Slavin, J. (2022). Food for Thought: Fibre intake for optimal health: How can healthcare professionals support people to reach dietary recommendations? The BMJ, 378. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2020-054370

[28] Zhang, S., Liu, X., Wu, J., Wang, H., Liu, H., Dong, C., Kuai, T., You, L., & Xiao, J. (2023). Association of dietary fiber with subjective sleep quality in hemodialysis patients: A cross-sectional study in China. Annals of Medicine, 55(1), 558-571. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2176541

[29] St-Onge MP, Roberts A, Shechter A, Choudhury AR. Fiber and saturated fat are associated with sleep arousals and slow wave sleep. J Clin Sleep Med, 2016;12(1):19%u201324. DOI: 10.5664/jcsm.5384

[30] Wang, X., Song, F., Wang, B., Qu, L., Yu, Z., & Shen, X. (2023). Vegetarians have an indirect positive effect on sleep quality through depression condition. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33912-7

[31] Wirth, J., Lin, K., Brennan, L., Wu, K., & Giovannucci, E. (2024). Protein intake and its association with sleep quality: Results from 3 prospective cohort studies. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78(5), 413-419. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-024-01414-y

[32] Goldschmied, J. R., Cheng, P., Kemp, K., Caccamo, L., Roberts, J., & Deldin, P. J. (2015). Napping to modulate frustration and impulsivity: A pilot study. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 164–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.013

[33] Romdhani, M., Dergaa, I., Moussa-Chamari, I., Souissi, N., Chaabouni, Y., Mahdouani, K., Abene, O., Driss, T., Chamari, K., & Hammouda, O. (2021). The effect of post-lunch napping on mood, reaction time, and antioxidant defense during repeated sprint exercice. Biology of sport, 38(4), 629–638. https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2021.103569

[34] Shaikh, N., & Coulthard, E. (2019). Nap‐mediated benefit to implicit information processing across age using an affective priming paradigm. Journal of Sleep Research, 28(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12728

[35] Liu, Y., Peng, T., Zhang, S., & Tang, K. (2018). The relationship between depression, daytime napping, daytime dysfunction, and snoring in 0.5 million Chinese populations: Exploring the effects of socio-economic status and age. BMC Public Health, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5629-9

[36] Pacheco, D. (2024). Does napping impact your sleep at night? Sleep Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.sleepfoundation.org/how-sleep-works/does-napping-impact-sleep-at-night